The symbol of Baracca

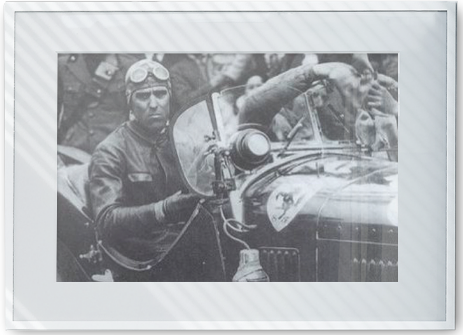

On 17 June 1923 the pilot Enzo Ferrari had the first of his few victories: in total they would be nine, over a career that has spanned, including withdrawals and returns, until 1931.

To the emotions behind the steering wheel, "the men agitator," as he liked to call, he has soon preferred the temptations of another dimension: the car. This Enzo has understood perfectly. He could deal with cars even without physically driving them. Indeed, to that day, June 17, 1923, is linked an episode that would play a decisive role in Ferrari’s passage from story to legend.

Because Ferrari, behind the apparent exclusive focus on 'doing', was in fact a master of appreciation the value of symbols, their ability to generate enthusiasm, becoming a reference point for passions of ordinary people. Having crossed the finish line behind the wheel of an Alfa Romeo RL 3000, Enzo got the prize for victory and congratulations from the organizers of the Circuit of Savio, a competition that would become popular in Romagna, and was approached by a distinguished gentleman.

Out of politeness he stopped to listen, while the mechanic who had accompanied him in the car, Giulio Ramponi, hurried him: "Come on, we must go back home...". Though that distinguished gentleman was none other but Enrico Baracca.

A Count whom the First World War firstly gave the glory and then inflicted the most cruel pain.

His son Francesco, had become, in rural Italy at the turn of the century, a myth: an aviation pilot, the hero of the skies, the flying symbol of a patriotism which Enzo, an ardent interventionist in 1915, was fully identified with. The activities of Baracca had a tragic outcome: he was shot down by the enemy in the clouds above Montello.

Il simbolo di Baracca

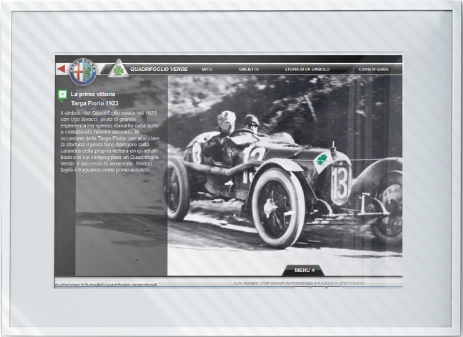

Il 17 giugno 1923 il pilota Enzo Ferrari conquista la prima delle sue non numerose vittorie: saranno in tutto nove, nell'arco di una carriera durata, fra ritiri e ritorni, fino al 1931. Alle emozioni del volante, «l'agitatore di uomini», come amava definirsi, aveva presto preferito le tentazioni di un'altra dimensione: di automobili. Questo Enzo l'aveva compreso perfettamente, ci si poteva occupare anche senza guidarle fisicamente verso il trionfo. Ma a quella data, il 17 giugno 1923, è legato un episodio che, nel viaggio del personaggio dalla storia alla leggenda, giocherà un ruolo decisivo. Perché Ferrari, dietro l'apparente esclusiva attenzione al «fare», era in realtà un maestro nell'intuire il valore dei simboli, la loro capacità di generare entusiasmi, trasformandosi in punti di riferimento per le passioni della gente comune. Tagliato il traguardo al volante di un'Alfa Romeo RL 3000, intascato il premio per la vittoria e le congratulazioni degli organizzatori del circuito del Savio, una competizione che in Romagna sarebbe diventata popolare, Enzo viene avvicinato da un distinto signore. Per educazione si ferma ad ascoltarlo, mentre il meccanico che in macchina lo aveva accompagnato verso la vittoria, Giulio Ramponi, gli mette fretta: «Su, andiamo, dobbiamo tornare verso casa...».Ma quel distinto signore altri non è che Enrico Baracca. Un conte cui la Prima guerra mondiale aveva prima dato la gloria e poi inflitto il più crudele dei dolori. Suo figlio, Francesco, era diventato, nell'Italia rurale di inizio secolo, un mito: pilota di aviazione, era l'eroe dei cieli, era il simbolo volante di un patriottismo nel quale Enzo, ardente interventista nel 1915, si era pienamente identificato. Le imprese dì Baracca avevano avuto un epilogo tragico: era stato abbattuto dal nemico tra le nuvole sopra Montello.

About Francesco Baracca and his courage, Ferrari received testimony also from his brother Dino, who in his letters from the front spoke with enthusiasm of the aviator who terrorized the Austrians. Standing in front of his father meant, for Enzo, to retrieve the thread of the past that he could not and did not want to forget.

Between the two men arose a friendship, soon extended on the hero's mother.

It was she, Paolina, who gave Ferrari the symbol which would forever be associated with the activity of the entrepreneur from Modena. One day Mrs. Baracca told Enzo “Ferrari, put on your cars the prancing stallion of my son.

It will bring you luck." Surely, even more than the mother of Francesco could imagine. As a gift commemoration, a photograph was taken, from which Enzo has never separated.

"The Horse" Ferrari wrote in his memoirs, "was and has remained black. I added the canary yellow background, which is the color of Modena."

Interestingly, only nine years after the chance meeting at the victory of the Circuit of Savio, the prancing horse would make his first appearance on the Enzo’s cars. The "debut" took place in Belgium, more precisely in Spa, where on July 10, 1932 was a 24 Hour race. The emblem was stuck on the hood of the 8-cylinder Alfa Romeo 2300 MM.

Why has Ferrari been waiting so long? Why has not sported the prancing stallion at least since the beginning of the team bearing his name, that is since 1929? Critics popularized a number of versions designed to irritate the persons concerned.

Di Francesco Baracca e del suo coraggio, Ferrari aveva ricevuto testimonianza anche dal fratello Dino, che nelle sue lettere dal fronte aveva parlato con entusiasmo dell'aviatore che terrorizzava gli austriaci. Trovarsi davanti il padre significava, per Enzo, recuperare il filo di un passato che non poteva e non voleva dimenticare. Tra i due uomini nacque un sentimento di amicizia, presto esteso alla madre dell'eroe. E fu lei, Paolina, a con segnare a Ferrari il simbolo al quale sarebbe stata per sempre associata l'attività dell'intraprendente modenese. Un giorno la signora Baracca disse a Enzo: «Ferrari, metta sulle sue macchine il cavallino rampante del mio figliolo. Le porterà fortuna». Sicuramente persino più di quanta la madre di Francesco potesse immaginare. A testimonianza del dono, venne scattata una fotografia, dalla quale Enzo non si separò mai. «Il cavallino» scrisse Ferrari nelle sue memorie «era ed è rimasto nero; io aggiunsi il fondo giallo canarino, che è il colore di Modena.»

Curiosamente, soltanto nove anni dopo il fortuito incontro sul traguardo del circuito del Savio il cavallino rampante avrebbe fatto la sua comparsa sulle vetture di Enzo. Il «debutto» avvenne in Belgio, per la precisione a Spa, dove il 10 luglio 1932 si correva una 24 Ore. Il marchio venne appiccicato sul cofano delle Alfa Romeo otto cilindri 2300 MM. Perché Ferrari aspettò tanto a lungo? Come mai non sfoggiò il cavallino rampante quantomeno sin dagli esordi della scuderia che portava il suo nome, cioè dal 1929? I detrattori divulgarono una serie di versioni destinate ad irritare moltissimo il diretto interessato.

Secondo una ricostruzione poi smentita dalle autorità militari dell'epoca, l'intera squadriglia 912, della quale Baracca faceva parte, aveva come emblema il famoso cavallino. A Enzo piaceva e semplicemente se ne appropriò, peraltro premurandosi di chiedere l'assenso della famiglia dell'aviatore, che di quella squadriglia era diventato, in vita e in morte, il personaggio più rappresentativo. Un'altra teoria, invece, rispetta la versione data da Ferrari, ma fissa in Germania l'origine del cavallino rampante (Michael Schumacher non ne sarà dispiaciuto...). Le cose sarebbero andate così. Il cavallino rampante è il simbolo della città di Stoccarda. Durante la Prima guerra mondiale, in un duello aereo, Francesco Baracca avrebbe abbattuto un velivolo di fabbricazione tedesca. Recuperando i resti del nemico, il pilota italiano si sarebbe impossessato del marchio che appariva sulla carlinga dell'aeroplano, costruito in una officina di Stoccarda. Nulla di strano nel comportamento di Baracca, era prassi tra gli aviatori recuperare, se possibile, qualcosa che testimoniasse il buon esito della battaglia nei cieli. Affezionatosi al simbolo, Francesco ne avrebbe poi fatto il proprio portafortuna. E dopo la sua fine il cavallino rampante sarebbe stato spedito ai genitori. Da loro passò nelle mani di Enzo.

According to a reconstruction denied later by the military authorities at that time, the entire squadron 912, to which belonged Baracca, had as its emblem the famous horse.

Enzo liked and simply appropriated it, however, he took care to seek the consent of the aviator’s family, whose son become, either in life or in death, the most representative person of the squadron. Another theory complies with the version given by Ferrari, but establishes in Germany the origin of the prancing horse (Michael Schumacher would not mind...). Things would be going as following.

The prancing stallion is the symbol of the city of Stuttgart. During the First World War, in an aerial duel, Francesco Baracca shot down an aircraft manufactured by Germany. Recovering the enemy aircraft wrecks, the Italian pilot would keep the badge attached to the plane’s fuselage, made in a factory in Stuttgart.

There was nothing strange in the behavior of Baracca, it was a practice among aviators to recover, if possible, something that would confirm the good result of the battle in skies. Affectionate to the symbol, Francesco would make it his own good-luck token. And after his death the prancing horse would be sent to his parents. From them it passed into the hands of Enzo.

As he was holding that 'badge' in a drawer, Ferrari was expanding its range of impact. The strategy he had in mind was very clear: its identification with the Alfa Romeo did not have to reduce it to the role of mere executor of the decisions of others. His personality was getting stronger day by day. No one like him understood about cars and about people. He was the first to realize that the senator Agnelli would withdraw Fiat from races.

He also realized that the same Alfa, sooner or later, would feel the need to entrust the sector of competitions to someone not overburdened with heavy industrial tasks. He was preparing himself for this role. And he knew he would not encounter any obstacles; a little bit pilot and a little bit manager, had the opportunity to beat everyone. He was the best, even at business. He kept selling cars between Emilia, Romagna and Marche.

Participating in races, though he felt himself not as good as he used to be, was useful to increase turnover of the dealership. "In 1927," he admitted, "I started races again because of the passion for sport and because of technical and commercial interests."

The passion for sport was a half-truth, in reality prevailed a wish to consolidate the business.

Even in that he anticipated times. As an industrialist, he would not spend a penny on advertising, his racing cars would be the only promotion tool. Previously, he had sporadically run to attract customers. His name was becoming a guarantee.

Among the firsts to understand the Enzo’s intentions was a director of Pirelli, Mario Lombardini, who was representing the Milanese company in England.

Ferrari did not like to travel abroad, nevertheless he took advantage to establish important relationships during the 'international' missions on duty of Rimini. Enzo went across the Channel once; the meeting with Lombardini excited him. He found a partner that fully shared his understanding of car racing, the constant affirmation of an unbreakable bond between racing and the mass production. Between them has been developed a friendship that led Ferrari to consider Lombardini even "a second father." Among friends of Pirelli, Lombardini was thought to be impressed by Ferrari; that Italian would certainly do something good, he was driven by a passion that could not be satisfied by being just a dealer.

This was also noticed by Peppino Verdelli, a young man who agreed to be his mechanic at the Modena Circuit. In the spring of 1927, Enzo stood a fair chance of winning his home race. He enrolled with a 6-cylinder Alfa Romeo 1500 SS. His countrymen were convinced that Ferrari had no chance as the other race cars were much more powerful than his one. However, at least once, the saying "nemo propheta in patria" has been disproved: the best knowledge of the track and the unexpected help of the rain led Enzo to victory. "You did bring me luck," Ferrari said to Peppino on the podium.

Mentre teneva quel «marchio» in un cassetto, Ferrari ampliava il suo raggio d'azione. La strategia che aveva in mente era chiarissima: l'identificazione con l'Alfa Romeo non doveva ridurlo al ruolo di mero esecutore di decisioni altrui. La personalità dell'individuo si andava rafforzando di giorno in giorno. Nessuno come lui capiva di macchine e di uomini. Era stato il primo ad intuire che il senatore Agnelli avrebbe allontanato la Fiat dalle corse. Si rendeva conto che la stessa Alfa, presto o tardi, avrebbe avvertito l'esigenza di affidare il settore agonistico a qualcuno non afflitto da pesanti incombenze industriali. Lui si stava preparando per il ruolo nel quale sapeva non avrebbe incontrato ostacoli: un po' pilota e un po' manager, aveva avuto modo di «pesare» tutta la gente dell'ambiente. Era il migliore. Anche negli affari. Continuava a vendere macchine fra Emilia, Romagna e Marche. Iscriversi a qualche gara, sebbene come pilota si sentisse ormai dimezzato, gli faceva comodo per incrementare il fatturato della concessionaria. «Nel 1927» ammise «ripresi a correre per entusiasmo sportivo e a causa di interessi tecnici e commerciali.» L'entusiasmo sportivo è una mezza bugia: in realtà prevaleva il desiderio di consolidare il business. Anche in questo anticipava i tempi. Da industriale non avrebbe speso una lira in pubblicità: le sue automobili da corsa sarebbero state l'unico veicolo promozionale. In precedenza, sporadicamente aveva fatto il corridore per attrarre clienti. Il suo nome stava diventando una garanzia.

Tra i primi a capire le intenzioni di Enzo fu un dirigente della Pirelli: Mario Lombardini rappresentava la casa milanese in Inghilterra. Ferrari non amava viaggiare all'estero, ma approfittava delle missioni «internazionali» affidategli da Rimini per allacciare importanti relazioni personali. Oltre Manica Enzo andò una sola volta: l'incontro con Lombardini lo entusiasmò. Trovò un interlocutore che pienamente condivideva il suo modo di intendere l'automobilismo sportivo, l'affermazione costante di un legame indissolubile tra le competizioni e la produzione di serie. Tra i due si sviluppò un'amicizia che spinse Ferrari a definire Lombardini addirittura «un secondo padre». Agli amici della Pirelli, Lombardini confidò di essere rimasto impressionato: sicuramente quel modenese avrebbe combinato qualcosa, era animato da una passione che non si sarebbe esaurita in una concessionaria...

Se ne accorse anche Peppino Verdelli, un giovanotto che aveva accettato di fargli da meccanico per il circuito di Modena. Nella primavera del 1927, a Enzo si presentò l'occasione di vincere la gara di casa. Si iscrisse con un'Alfa Romeo 1500 SS sei cilindri. I suoi compaesani erano convinti che Ferrari non avesse chance, alla corsa partecipavano vetture molto più potenti della sua. Ma per una volta il detto «nemo propheta in patria» venne smentito: la migliore conoscenza del tracciato e l'insperato aiuto della pioggia proiettarono Enzo verso il trionfo. «Mi hai portato fortuna», disse Ferrari a Peppino sul podio delle premiazioni.

Non si lasciarono più: Verdelli ne fu per decenni il fedelissimo autista, ma anche il confidente. Enzo gli diede simbolicamente il ruolo che era stato di Sivocci: quello di fratello ideale.

Leo Turrini (2002)

They did not leave each other. Verdelli has been for decades his most faithful driver, but also the soul mate. Enzo gave him a symbolic role of SIVOCCI, that of his ideal brother.

Leo Turrini (2002)

[Translated by Sylwia Kowalczyk]